One of the running questions in Mets spring training this year has been, the way it's phrased, whether Juan Lagares or Eric Young, Jr. should be the team's third starting outfielder. The assumption is that the first two are Curtis Granderson, the Mets' biggest free agent signing since Jason Bay, and Chris Young, one of their other notable signings of the off-season. Phrased that way, the answer is obvious: Lagares should start. Last year, while hitting .242/.281/.352 (an OPS+ of 80, well below league average), Lagares was worth something in excess of 3 wins above replacement. Since that was in just 421 plate appearances, he was a couple of wins above average. His defense is ridiculous, making him an incredibly productive player even if we regress the defense a little bit. Eric Young, meanwhile, even after coming to the Mets (when his performance improved) was in that zone between average and replacement-level. He was a passable left fielder, though not deserving of his Gold Glove nomination, but really his only virtue was his speed, and though he was a great baserunner last year there's a limit to how valuable that is if it's all you offer. The argument for Young to start is just that Terry Collins wants a base-stealer at the top of the lineup. Well, Lagares has the same base-stealing numbers as EYJ this spring, 3 SB/1 CS, and as he's not likely to be outhit at the plate by Young there's no reason to think he'd be a worse leadoff hitter.

Saturday, March 29, 2014

Friday, March 28, 2014

Everything Went Bad in 1973

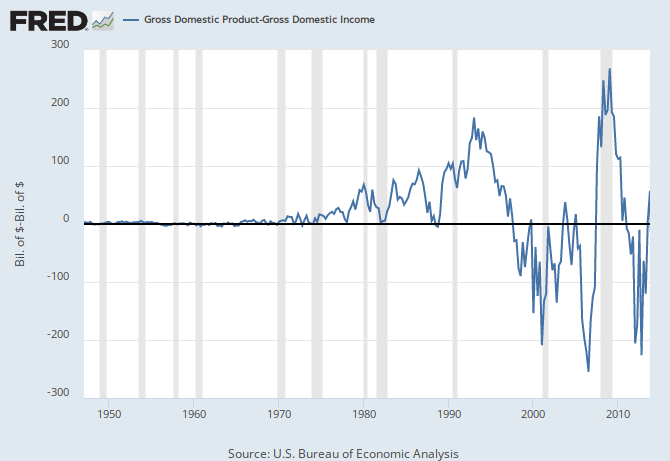

One of the things I learned during my four years of undergraduate higher education is that 1973 is where everything started to go wrong. In just about every time series of social data, that's the turning-point, where things stopped getting better or started getting worse or both. Stuff like economic inequality, incarceration rates, various aspects of race relations, etc. But I was kind of surprised to see that the same seems to be true of the relationship between Gross Domestic Product and Gross Domestic Income. The two are, by definition, identical, but we measure them separately. We would, obviously, like to see the two measures stick pretty close to one another. Here's a time series of GDP - GDI (courtesy of Matt Yglesias):

The moment when it starts diverging from the zero line is, you guessed it, 1973. Seriously, that's when everything went wrong. Fundamental economic identities started breaking down! Richard Nixon really did a number on the world.

I'll note that I'm less than 100% certain in this diagnosis. The chart isn't in proportional form, and obviously GDP has been growing steadily, especially nominal GDP. So it's possible that, pre-1973, it was fluctuating around zero just as much as it has seemed to be later, as a proportion of the total figure. My sense is that this isn't the case, but without having actual numbers in front of myself I can't be confident in that belief. (Very roughly I think I get that a disparity as large as the -$230 billion or so from around 2005 would've been something like $17 billion in the years before 1970, and the +$180 billion from around 1992 is a bit bigger than that, and it doesn't look like there were any divergences that big, but that's based on eyeballing squiggly lines and thus comes with massive confidence intervals.)

So I think this is yet another extreme example of how 1973 is when everything started going bad, but I'm not completely certain.

The moment when it starts diverging from the zero line is, you guessed it, 1973. Seriously, that's when everything went wrong. Fundamental economic identities started breaking down! Richard Nixon really did a number on the world.

I'll note that I'm less than 100% certain in this diagnosis. The chart isn't in proportional form, and obviously GDP has been growing steadily, especially nominal GDP. So it's possible that, pre-1973, it was fluctuating around zero just as much as it has seemed to be later, as a proportion of the total figure. My sense is that this isn't the case, but without having actual numbers in front of myself I can't be confident in that belief. (Very roughly I think I get that a disparity as large as the -$230 billion or so from around 2005 would've been something like $17 billion in the years before 1970, and the +$180 billion from around 1992 is a bit bigger than that, and it doesn't look like there were any divergences that big, but that's based on eyeballing squiggly lines and thus comes with massive confidence intervals.)

So I think this is yet another extreme example of how 1973 is when everything started going bad, but I'm not completely certain.

Monday, March 24, 2014

On Reasonable Doubt and Probability

One of the lingering philosophical questions in law generally but in criminal law in particular is whether the various burdens of proof, and the burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt in particular, are, in some underlying sense, probabilistic. We interpret everything probabilistically these days; sophisticated websites offer projected outcomes for an upcoming baseball season expressed in tenths of a win, explicitly to make the point that they're probabilistic averages, not predictions of a specific final win total. But we are naturally a little uncomfortable convicting someone on that basis, a discomfort rooted in the old phrase "to a moral certainty," the forebear of "beyond a reasonable doubt." Is a 10% probability of the defendant's innocence "reasonable doubt"? Is 1%? Do we really think that we convict people with 99% probabilities that they're guilty? Do we really want to start thinking about this? But isn't it the correct way to think about it, in at least some senses?

And I've just had an idea about a slightly different way to phrase this question, if not to answer it, based on the facts of a case I'm just starting to read for my Evidence class. In this case, which bears the awesome name of People v. Mountain, a criminal defendant was convicted based, among other things, on evidence about blood type. There was type A blood at the crime scene, and the defendant was type A. Type A blood is found in roughly one-third of people, a little more in this country if we don't distinguish between positive and negative. Now, it is unambiguously true that knowing there was type A blood at the scene should make us more likely to believe that a type A defendant, any type A defendant in fact, is guilty. This is where Bayesian statistics come in handy; math below the fold.

Why Do We See Commercial Speech as a Free Speech Issue?

This is sort of a nebulous thought, but I've just come from my First Amendment class where we were discussing the issue of commercial speech, that is, how and when the government may regulate advertising more strictly than it regulates most communication. And... I've been kind of uneasy during the whole discussion. I'm pretty sure I agree with the result of the early cases, the Blackmun cases from around 1976 striking down wholesale prohibitions on advertising by certain professions (doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, etc.). But I also have a very strong gut reaction against the more recent cases, wherein the conservatives have taken the idea that commercial speech receives First Amendment protection and run wild with it in their usual corporatist direction. Say, for instance, the recent D.C. Circuit case striking down the latest batch of warning-label requirements for cigarettes. But of course that gut reaction lines up 100% with my policy preferences, and it's true that most of the arguments people make for distinguishing commercial speech from any other kind of speech fail. (The same is true of a lot of things that have traditionally been labeled "low-value" speech, like obscenity, say.) Thus the discomfort. But after getting home from class I had a thought that I'm not sure is right, or workable, but if it is would solve a lot of the problems I'm having justifying those instinctive reactions. Here it is:

Why are we treating this as a free speech issue at all? Take those cigarette labeling requirements, for instance. The government isn't exactly compelling anyone to speak. Rather the government is prohibiting anyone to sell cigarettes without engaging in a certain bit of speech. See the difference? It's easy to avoid the purported compulsion to speak; all you have to do is not sell cigarettes, which really is a good idea anyway 'cause cigarettes are evil. The same logic applies, of course, to the old "doctors can't advertise" laws: in a sense they're not really restricting anyone's speech, they're restricting people's ability to be doctors by conditioning being a doctor on agreeing not to exercise what might otherwise be a free speech right. Back at the higher level of generality, the point is that commercial speech is distinctive because entering into a certain line of commerce is a voluntary decision, and as the equal protection cases were quick to note, it's a lot less problematic when the government visits some disadvantage upon people who could have chosen not to be in a position to receive the disadvantage.

Now, assuming I'm right and that we can and perhaps should stop viewing these cases as being real First Amendment cases, that's a long way from the end of the analysis. Really it's the beginning of the analysis, and the analysis is going to strike a lot of stuff down, or it should anyway. Because the government is most emphatically not unlimited in its ability to restrict people's ability to pursue a certain line of commerce. It cannot say, for instance, that if you want to be a doctor you have to contribute to the campaign committee of the ruling party. It can't say that if you want to be a lawyer you have to sign an oath of belief in god. There is, in other words, some right to engage in economic activity without undue obstruction. But obviously there can be lots and lots of due obstructions; see generally all jurisprudence after 1937. So the question becomes, in essence, which restrictions on the ability to pursue a certain profession or what-have-you are reasonable, and which are not. This analysis should be basically located under the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, or in the Ninth Amendment if we're talking about the feds. It can also have a bit of an Equal Protection component to it. Both of those are of course really doctrinally difficult, since the Privileges or Immunities Clause was massacred by the Slaughter-House Cases and applying the Equal Protection Clause to economic regulations is, with good reason, generally considered a no-no. That's actually the point of Carolene Products, the footnote-in-history with the history-making footnote that spawned strict scrutiny. (Actually it's one tiny little point that the court makes in passing, but because of the footnote it's the only reason anyone remembers the case, heh.)

But the whole point here is to upend doctrine, and it strikes me as quite reasonable to say that the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States include some sort of economic rights, though not in as hard-core laissez-faire a way as what the Lochner Court thought. Determining the content of those rights, as with all unenumerated rights, is going to involve something resembling moral or political philosophy, to involve reasoning about which purported economic rights are really necessary in a free society and which are merely impediments to a free society's quest to govern itself. Some such distinction is obviously necessary: the government may ban the profession of hit-man, but it probably cannot ban the profession of doctor, I think, and certainly not of lawyer, though that has independent constitutional authority behind it. And somewhere around whatever distinctions we drew there would be drawn some line between the kinds of commercial speech regulations that are acceptable and those that are not. It feels right to me to say that telling lawyers they can't advertise is unreasonable but telling tobacco companies to do, well, anything is pretty damn reasonable. (They rank not very far above hit-men in my book, honestly.) Someone else might disagree, but I think that's the proper locus of the disagreement.

The entire language of economic rights is anathema, because of what it was used to do in the first third of the 20th century. But the fact that the Lochner Court abused the idea of economic rights doesn't mean there aren't any, or that they're not important. And I think that treating commercial speech as a form of economic right rather than as a First Amendment free speech right would be both theoretically more sound and would do a better job of protecting the relevant interests while not undermining society's ability to enact beneficial economic regulations.

Why are we treating this as a free speech issue at all? Take those cigarette labeling requirements, for instance. The government isn't exactly compelling anyone to speak. Rather the government is prohibiting anyone to sell cigarettes without engaging in a certain bit of speech. See the difference? It's easy to avoid the purported compulsion to speak; all you have to do is not sell cigarettes, which really is a good idea anyway 'cause cigarettes are evil. The same logic applies, of course, to the old "doctors can't advertise" laws: in a sense they're not really restricting anyone's speech, they're restricting people's ability to be doctors by conditioning being a doctor on agreeing not to exercise what might otherwise be a free speech right. Back at the higher level of generality, the point is that commercial speech is distinctive because entering into a certain line of commerce is a voluntary decision, and as the equal protection cases were quick to note, it's a lot less problematic when the government visits some disadvantage upon people who could have chosen not to be in a position to receive the disadvantage.

Now, assuming I'm right and that we can and perhaps should stop viewing these cases as being real First Amendment cases, that's a long way from the end of the analysis. Really it's the beginning of the analysis, and the analysis is going to strike a lot of stuff down, or it should anyway. Because the government is most emphatically not unlimited in its ability to restrict people's ability to pursue a certain line of commerce. It cannot say, for instance, that if you want to be a doctor you have to contribute to the campaign committee of the ruling party. It can't say that if you want to be a lawyer you have to sign an oath of belief in god. There is, in other words, some right to engage in economic activity without undue obstruction. But obviously there can be lots and lots of due obstructions; see generally all jurisprudence after 1937. So the question becomes, in essence, which restrictions on the ability to pursue a certain profession or what-have-you are reasonable, and which are not. This analysis should be basically located under the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, or in the Ninth Amendment if we're talking about the feds. It can also have a bit of an Equal Protection component to it. Both of those are of course really doctrinally difficult, since the Privileges or Immunities Clause was massacred by the Slaughter-House Cases and applying the Equal Protection Clause to economic regulations is, with good reason, generally considered a no-no. That's actually the point of Carolene Products, the footnote-in-history with the history-making footnote that spawned strict scrutiny. (Actually it's one tiny little point that the court makes in passing, but because of the footnote it's the only reason anyone remembers the case, heh.)

But the whole point here is to upend doctrine, and it strikes me as quite reasonable to say that the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States include some sort of economic rights, though not in as hard-core laissez-faire a way as what the Lochner Court thought. Determining the content of those rights, as with all unenumerated rights, is going to involve something resembling moral or political philosophy, to involve reasoning about which purported economic rights are really necessary in a free society and which are merely impediments to a free society's quest to govern itself. Some such distinction is obviously necessary: the government may ban the profession of hit-man, but it probably cannot ban the profession of doctor, I think, and certainly not of lawyer, though that has independent constitutional authority behind it. And somewhere around whatever distinctions we drew there would be drawn some line between the kinds of commercial speech regulations that are acceptable and those that are not. It feels right to me to say that telling lawyers they can't advertise is unreasonable but telling tobacco companies to do, well, anything is pretty damn reasonable. (They rank not very far above hit-men in my book, honestly.) Someone else might disagree, but I think that's the proper locus of the disagreement.

The entire language of economic rights is anathema, because of what it was used to do in the first third of the 20th century. But the fact that the Lochner Court abused the idea of economic rights doesn't mean there aren't any, or that they're not important. And I think that treating commercial speech as a form of economic right rather than as a First Amendment free speech right would be both theoretically more sound and would do a better job of protecting the relevant interests while not undermining society's ability to enact beneficial economic regulations.

Labels:

constitutional issues,

economics,

free speech,

law,

politics

Sunday, March 23, 2014

What Richard Posner Gets Wrong About Ideology

I'm reading an excerpt from Richard Posner's book How Judges Think for one of my classes, and I just came across the following passage:

My overall interpretation of ideological disagreements is that they're mostly about the fact that people have significantly different goals, values, and priorities from one another. Some of these differences are purely a matter of individual temperament and nature, differences in moral philosophy or what-have-you. Many derive from the fact that much of politics is a contest between the interests of different groups, and members of those groups have an understandable preference for their own side's interests. That's most of what was going on in the 1960s turmoil, for instance: society was set up in a way that put certain types of people in power and kept other types of people out of power, the disempowered types didn't like it, obviously, and started agitating to change it, and the people in power were not happy about the prospect of having their position challenged. You don't need any "different interpretations" to see why different kinds of people would react differently to the same events. It's like how people in Boston and in the Bronx had by and large opposite reactions to David Ortiz's various game-changing home runs in the 2004 ALCS: they were rooting for different teams. That's basically just a form of partisanship, which Posner rightly distinguishes from ideology, but in a sense they're not so different. I want the Mets to do well, on an essentially arbitrary basis; I want my own life to be a good one, for understandably simple reasons; and there are certain things that I would like to see happen on a purely moral basis. The origins of my preferences are different in each case, but the effect is the same: there's something I want to see happen, and I'm going to react to everything about the world based on how it affects those goals or desires.

For it is implausible that people are libertarians, or socialists, or originalists because libertarianism, or socialism, or originalism is "correct." They can't all be, and probably none is, except in severely qualified form. These isms, like religious beliefs, are indeed hypothesis-driven rather than fact-driven. Nothing is more common than for different people of equal competence in reasoning to form different beliefs from the same information. Think of how sophisticated people reacted to student riots protesting the Vietnam War in the late 1960s and early 1970s: some with horror, fearing social disintegration; others with exhilaration, hoping for transformative social change. They were seeing the same thing but interpreting it in different ways. Alternately they were reacting differently to the same information because of different intuitions, a kind of buried knowledge.This strikes me as basically wrong. It's part of something that I think is basically right, namely a justification of judicial use of personal ideology in reaching decisions in legally ambiguous cases. But this gets something wrong about ideology, I think, and it's a common thing for people to get wrong. His example is instructive, because the "social disintegration" that some feared and the "transformative social change" that others hoped for were of course the exact same thing. It's just that some people wanted it to happen and other people didn't. So liberal radicals and conservative traditionalists weren't really "interpreting" the riots differently, they just differed on whether they liked what was happening.

My overall interpretation of ideological disagreements is that they're mostly about the fact that people have significantly different goals, values, and priorities from one another. Some of these differences are purely a matter of individual temperament and nature, differences in moral philosophy or what-have-you. Many derive from the fact that much of politics is a contest between the interests of different groups, and members of those groups have an understandable preference for their own side's interests. That's most of what was going on in the 1960s turmoil, for instance: society was set up in a way that put certain types of people in power and kept other types of people out of power, the disempowered types didn't like it, obviously, and started agitating to change it, and the people in power were not happy about the prospect of having their position challenged. You don't need any "different interpretations" to see why different kinds of people would react differently to the same events. It's like how people in Boston and in the Bronx had by and large opposite reactions to David Ortiz's various game-changing home runs in the 2004 ALCS: they were rooting for different teams. That's basically just a form of partisanship, which Posner rightly distinguishes from ideology, but in a sense they're not so different. I want the Mets to do well, on an essentially arbitrary basis; I want my own life to be a good one, for understandably simple reasons; and there are certain things that I would like to see happen on a purely moral basis. The origins of my preferences are different in each case, but the effect is the same: there's something I want to see happen, and I'm going to react to everything about the world based on how it affects those goals or desires.

Saturday, March 22, 2014

Cosmos and Creationists

Back in 1980, Carl Sagan, noted astrophysicist and public-intellectual ambassador for science at large, ran a TV series on PBS called Cosmos, which presented a great deal of scientific knowledge about various cosmological issues for public consumption. It was highly successful. Earlier this year, Neil deGrasse Tyson, perhaps the closest thing to Sagan in today's popular culture, rebooted the series on FOX. The first few episodes have aired, and predictably, people who don't like what science has to tell us about these cosmological questions are not happy. According to this article, creationists are apparently trying to demand "equal time;" I can't tell whether they want that time on Cosmos itself or whether they want to be given a show of their own with which to answer NDT. Here's the money quote from some creationist guy:

And the evidence says that the universe as we know it goes back about 13.8 billion years, at which time everything in it was packed into an unimaginably small region, and immediately after which it underwent a period of extremely rapid inflation and has been expanding more gradually ever since. (In fact, we just got another big bunch of evidence supporting this explanation, which is pretty cool.) Now, there's stuff to be said about the ability of religious types to craft "yeah but god made it happen" responses to this kind of evidence, but that's not really the point. The point is that it's absurd for a bunch of people who happen to dislike what the universe has told us about its nature to demand that a science show, devoted to telling people what we know about the world, spend any significant amount of time talking about specific "alternate" theories about the universe that are known to be wrong. NDT can, and I believe did, spend a significant amount of time laying out all of the reasons why we know that the universe is 13.82 billion years old et cetera, and doing so implicitly states that any particularly literal Biblical creationist beliefs are wrong. That's the most those beliefs deserve from him.

I was struck in the first episode where [Tyson] talked about science and how, you know, all ideas are discussed, you know, everything is up for discussion –- it's all on the table -- and I thought to myself, 'No, consideration of special creation is definitely not open for discussion, it would seem.'The thing that's so striking about this is how very, very wrong it gets what having an open mind means for a scientist. What it means is that you don't rule out any ideas before you look at the evidence. What it most emphatically does not mean is that you don't rule out any ideas after you look at the evidence. If you can't rule things out after you look at the evidence, well, what's even the point of looking at evidence? Why bother having science at all? The whole point is to let the universe tell us what it's like. If, to use the incredibly-cliched comparison, we aren't allowed to conclude, after looking at all the evidence, that the earth is round and not flat, well, it's absurd to call what we're doing science. It's some kind of weird philosophy of how you can never really know anything, blah blah blah. To a scientist, the shape of the earth is an open question precisely until we actually observe something in the world which is only consistent with one particular answer.

And the evidence says that the universe as we know it goes back about 13.8 billion years, at which time everything in it was packed into an unimaginably small region, and immediately after which it underwent a period of extremely rapid inflation and has been expanding more gradually ever since. (In fact, we just got another big bunch of evidence supporting this explanation, which is pretty cool.) Now, there's stuff to be said about the ability of religious types to craft "yeah but god made it happen" responses to this kind of evidence, but that's not really the point. The point is that it's absurd for a bunch of people who happen to dislike what the universe has told us about its nature to demand that a science show, devoted to telling people what we know about the world, spend any significant amount of time talking about specific "alternate" theories about the universe that are known to be wrong. NDT can, and I believe did, spend a significant amount of time laying out all of the reasons why we know that the universe is 13.82 billion years old et cetera, and doing so implicitly states that any particularly literal Biblical creationist beliefs are wrong. That's the most those beliefs deserve from him.

Tuesday, March 11, 2014

The Living Constitution, Post-Script: Plessy v. Ferguson Edition

A brief follow-up to my previous post about how no one really believes in the living constitution. Steve Calabresi liked to say, in the class I took with him about constitutional theory, that the first task of any good constitutional theory is to explain why Brown v. Board of Education is correct. Brown is in many ways the center-piece of the modern constitutional understanding and its relationship to society; any theory which views it as erroneous has, therefore, a fatal weakness. But I've often had the thought, especially when reading anything written by Bruce Ackerman but also when reading Jack Balkin's Living Originalism, that this is only half of the test. I don't just want a theory to tell me why Brown is correct. I want it to tell me why Plessy v. Ferguson was wrong. Now, that might sound like the same thing, since the one overturned the other. But I mean that I want a theory to tell my why Plessy has always been wrong, why it was wrong the day it was decided. Partly that's because I believe it was wrong the day it was decided. Partly that's because I think it's important that it was wrong the day it was decided. If we think Brown is right, and that it's important that it's right, which we do, I think it equally important to state clearly that the contrary result could never be the correct one under our Constitution. If Plessy was not really wrong the day it was decided, then the Fourteenth Amendment, which we think of as guaranteeing racial equality, does not really do so, because somehow Plessy was consistent with it, once upon a time.

So I found it very interesting when the article from which I drew the Newtonian-vs.-Darwinian imagery later described the holding of the Brown case thusly:

But I actually think this is a perfect example of my point from my last post. Because, really? Do we really think anyone believed that? That Earl Warren did? That William Brennan did? That they thought the problem with Plessy was just that it had become outdated? I know that the architect of the Brown case, Thurgood Marshall, didn't think Plessy was correct. He was the leader of an organized movement that had been working to undermine and eventually overturn Plessy for more than half of the time between the two cases. Of course he thought Plessy had been wrong the day it was decided. Certainly my grandfather, who defended the Brown case on traditional legal grounds during the controversy it generated, though Plessy had been wrong, and obviously so. Do we really think that Warren, Brennan, Hugo Black, Felix Frankfurter thought that Louisiana's railroad segregation laws of the 1890s were constitutional? I don't think they did. I just don't buy it. I think they all thought that racial segregation was and had always been a denial of the equal protection of the laws.

But that isn't what they said. Instead they couched their opinion in the terms of a living constitution, for some reason. One way or another, they didn't want to condemn the past as strongly as their own opinions would condemn it. Which was arguably a mistake. After all, the living constitution idea, or at least what people usually mean by that phrase, really is a philosophically weak idea. It opens you up to the attack of people like Antonin Scalia and Herbert Weschler, who'll accuse you of judicially rewriting the Constitution. Better to just say, no, the ones who rewrote the Constitution were the Plessy Court, who struck out the Equal Protection Clause from the document. It might make the immediate firestorm worse, as those on the other side castigate you for repudiating their past, but in the long run I think it would lead to a more solid theoretical foundation for the new constitutional understanding.

So I found it very interesting when the article from which I drew the Newtonian-vs.-Darwinian imagery later described the holding of the Brown case thusly:

Not that Plessy v. Ferguson was wrong in 1896, the Court argued, but rather Plessy v. Ferguson had become erroneous because of what separate but equal had come to represent.The Court, in other words, rejected my view. Plessy wasn't wrong at the time, but it became wrong, as the meaning of segregation changed or perhaps as we just grew to understand that meaning better.

But I actually think this is a perfect example of my point from my last post. Because, really? Do we really think anyone believed that? That Earl Warren did? That William Brennan did? That they thought the problem with Plessy was just that it had become outdated? I know that the architect of the Brown case, Thurgood Marshall, didn't think Plessy was correct. He was the leader of an organized movement that had been working to undermine and eventually overturn Plessy for more than half of the time between the two cases. Of course he thought Plessy had been wrong the day it was decided. Certainly my grandfather, who defended the Brown case on traditional legal grounds during the controversy it generated, though Plessy had been wrong, and obviously so. Do we really think that Warren, Brennan, Hugo Black, Felix Frankfurter thought that Louisiana's railroad segregation laws of the 1890s were constitutional? I don't think they did. I just don't buy it. I think they all thought that racial segregation was and had always been a denial of the equal protection of the laws.

But that isn't what they said. Instead they couched their opinion in the terms of a living constitution, for some reason. One way or another, they didn't want to condemn the past as strongly as their own opinions would condemn it. Which was arguably a mistake. After all, the living constitution idea, or at least what people usually mean by that phrase, really is a philosophically weak idea. It opens you up to the attack of people like Antonin Scalia and Herbert Weschler, who'll accuse you of judicially rewriting the Constitution. Better to just say, no, the ones who rewrote the Constitution were the Plessy Court, who struck out the Equal Protection Clause from the document. It might make the immediate firestorm worse, as those on the other side castigate you for repudiating their past, but in the long run I think it would lead to a more solid theoretical foundation for the new constitutional understanding.

The "Living Constitution" and Repudiating the Past

An article I'm reading about the failed nomination of Robert Bork to the Supreme Court describes the debate over the "living constitution" as one between "an eighteenth century Newtonian Constitution and a nineteenth century Darwinian Constitution." The idea is to contrast the timeless, unchanging nature of Newtonian physics with the kind of gradual evolutionary change identified with Darwin. Kind of at random, this is a perfect metaphor for a point I've been planning on writing into a post for the past several days. The key point is this: Newton was wrong about stuff! Not, actually, wrong about the idea that the laws of physics are unchanging throughout time; as best I know, that part is true. But he got a lot of the laws of physics wrong. The universe only looks the way Newton thought it did at a very superficial level. Our ideas about the universe are very, very different now than they were in 1727, not because the universe has changed but because we just understand it better.

How does this relate to the living constitution? Well, it should be kind of obvious, but now I'll approach from the other side and make the point I've been wanting to make for a while. I don't think anyone really believes in the "living constitution." At least, I think a lot of people who purport to believe it don't really, not if its taken literally. Not if it's taken to mean that the Constitution itself changes over time. Bruce Ackerman sure seems to believe that, but I doubt that someone like William Brennan did. Rather, I think he thought that a lot of existing constitutional doctrine was dead wrong. He, therefore, wanted to issue decisions on constitutional issues that were not remotely consistent with the current or pre-existing understanding of the Constitution. But it's always controversial when the Court repudiates one of its existing precedents, and would doubtless be many times more so when it repudiates a whole complex of constitutional theory. So instead of saying that the old understanding was wrong, he, and those similarly minded, talk about how the Constitution needs to adapt with the times, or whatever.

In other words, the "living constitution" is an idea that people make up to avoid having to be honest about how much they're repudiating the past. We're very proud of our past, and rightly so in a lot of ways. Scientists are very proud of their past, too. But scientists don't see any problem saying that Isaac Newton was a great man and that he was dead wrong about a whole lot of things. This is perhaps one of the downsides to the eminently justified demise of legal scientism, the belief that human laws were like the laws of nature and had only to be discovered through the exercise of reason. (I get the impression that the legal scientists put more emphasis on reason than on experiment or observation, interestingly.) In that framework, it would make complete sense to say, well, the views of a century ago were just plain wrong, and we're not going to follow them even though we don't think the underlying truth has changed. The legal realists rightly attacked the view of law as an abstract, timeless entity, as opposed to the product of ongoing human politics. And, I think, after their triumph it was just easier, more comfortable, to see the Constitution as evolving over time than to say that the constitutional understandings of prior generations were wrong. And so emerged the living constitution, to say that, well, perhaps the past wasn't wrong for the past, but it would be wrong for the present. It lets us gloss over the continuity errors in our Dworkinian chain novel. But we know the errors are there, we put them there on purpose, because we like the new version of the story better than the old one, we just don't quite want to admit it.

Oh, and as an aside, it's worth pointing out that Darwinian evolution unquestionably occurs within a universe governed by timeless physical laws. In fact, Richard Dawkins has suggested that evolution by natural selection is a timeless law of nature, that life anywhere in the universe would proceed by it. There is no inconsistency between evolution and physics, and of course none of this has anything to do with the way we update our scientific understanding of the universe. Also, individual organisms don't evolve, they develop, the Constitution could only "evolve" in a properly Darwinian sense if the change took place over several different versions of it. A Jeffersonian world, where the constitution expired every twenty years, would feature such evolution; ours cannot, even under a "living constitutional" view. But all of that is nit-picking and not really about the legal stuff.

How does this relate to the living constitution? Well, it should be kind of obvious, but now I'll approach from the other side and make the point I've been wanting to make for a while. I don't think anyone really believes in the "living constitution." At least, I think a lot of people who purport to believe it don't really, not if its taken literally. Not if it's taken to mean that the Constitution itself changes over time. Bruce Ackerman sure seems to believe that, but I doubt that someone like William Brennan did. Rather, I think he thought that a lot of existing constitutional doctrine was dead wrong. He, therefore, wanted to issue decisions on constitutional issues that were not remotely consistent with the current or pre-existing understanding of the Constitution. But it's always controversial when the Court repudiates one of its existing precedents, and would doubtless be many times more so when it repudiates a whole complex of constitutional theory. So instead of saying that the old understanding was wrong, he, and those similarly minded, talk about how the Constitution needs to adapt with the times, or whatever.

In other words, the "living constitution" is an idea that people make up to avoid having to be honest about how much they're repudiating the past. We're very proud of our past, and rightly so in a lot of ways. Scientists are very proud of their past, too. But scientists don't see any problem saying that Isaac Newton was a great man and that he was dead wrong about a whole lot of things. This is perhaps one of the downsides to the eminently justified demise of legal scientism, the belief that human laws were like the laws of nature and had only to be discovered through the exercise of reason. (I get the impression that the legal scientists put more emphasis on reason than on experiment or observation, interestingly.) In that framework, it would make complete sense to say, well, the views of a century ago were just plain wrong, and we're not going to follow them even though we don't think the underlying truth has changed. The legal realists rightly attacked the view of law as an abstract, timeless entity, as opposed to the product of ongoing human politics. And, I think, after their triumph it was just easier, more comfortable, to see the Constitution as evolving over time than to say that the constitutional understandings of prior generations were wrong. And so emerged the living constitution, to say that, well, perhaps the past wasn't wrong for the past, but it would be wrong for the present. It lets us gloss over the continuity errors in our Dworkinian chain novel. But we know the errors are there, we put them there on purpose, because we like the new version of the story better than the old one, we just don't quite want to admit it.

Oh, and as an aside, it's worth pointing out that Darwinian evolution unquestionably occurs within a universe governed by timeless physical laws. In fact, Richard Dawkins has suggested that evolution by natural selection is a timeless law of nature, that life anywhere in the universe would proceed by it. There is no inconsistency between evolution and physics, and of course none of this has anything to do with the way we update our scientific understanding of the universe. Also, individual organisms don't evolve, they develop, the Constitution could only "evolve" in a properly Darwinian sense if the change took place over several different versions of it. A Jeffersonian world, where the constitution expired every twenty years, would feature such evolution; ours cannot, even under a "living constitutional" view. But all of that is nit-picking and not really about the legal stuff.

Tuesday, March 4, 2014

The Poverty Trap's Assumed Explotation

Paul Krugman has a very nice series of blog posts attacking Paul Ryan's latest discussion of poverty, which continues in his usual theme of how anti-poverty programs are actually terrible for the poor. The series culminates in this post, pointing out that not only does Ryan's attempt to invoke scholarship fail miserably, but the logical argument he's trying to make with that scholarship is equally a failure. Ryan loves to focus on the issue of "social mobility," but he simply assumes that reducing the incentives of the poor to work hard will reduce their social mobility. There is in fact no evidence for this assumption: internationally, we observe that the American poor, having a less-generous welfare state upon which to depend than their European brethren, indeed work harder, as Ryan thinks they should, and also have worse social mobility. Oops.

What Paul Krugman did not say is what's behind this assumption of Ryan's. And what I think it is is the idea that people, or poor people in any case, should only and will only be permitted to live a non-destitute life if they work really hard. It's kind of the old "deserving poor" idea, that poor people deserve their poverty and do not deserve charity (private or public in nature) unless they have a good Protestant work ethic (and, particularly in the olden days, various other good moral qualities). So then for somebody like Paul Ryan, it becomes definitionally true that getting a poor person to work less hard will disadvantage them, because we're assuming that only working hard can permit a poor person to stop being destitute. And so public policies which in fact weaken or destroy the empirical connection between hard work and being allowed to live a marginally-comfortable life must be disadvantaging the poor, even if in fact they make them less poor. Because after all, the only way to get ahead is by working hard, even if that isn't true.

Now, obviously, that's ridiculous. So what's going on? One possibility is that Paul Ryan and his ilk believe their own hype somehow. Could be. More likely, though, is one of the following two options, or some admixture of the two. One would be an essentially theological belief: it doesn't matter how comfortable a life poor people are allowed to live here on earth. Living a life of dependency on the government will be bad for their souls, and will therefore condemn them to an eternity of torment in hell upon their deaths. We shouldn't be tempting people into laziness by making it possible for them to live somewhat more lazy lives without material punishment within the temporal realm. This is of course a somewhat-logically-consistent position (although Republican doctrine doesn't exactly avoid providing similar temptations for the rich and powerful, and there's probably nothing whatsoever in the Bible to support this view anyway, perhaps unique among all possible theological or moral views), but it rather blatantly violates the principle that public policy ought not be used as a tool to save others' souls according to one's own theology.

On a more crass level, Paul Ryan doesn't care about poor people at all. What he cares about is extracting work from them, because he is the representative of the capitalist classes. And it is of course perfectly true that if our social goal is extracting the most work from the poor, well yeah, things that reduce the incentive of the poor to work hard and which thereby have the effect of reducing working hours among the working poor are bad. But this is not exactly a social goal that Paul Ryan can be upfront about. So he needs to disguise his nakedly exploitative desire to extract the maximum work-hours from the peasantry by pretending to have a background assumption that working harder is unavoidably the only way for a poor person to move up in the world and to have a better life. That gives him an excuse to pursue policies dedicated precisely to making that the true state of the world, while pretending that he cares about poor people.

Now, I don't know which of these is actually motivating Paul Ryan. I suspect it's about 70%, maybe closer to 80% the class warfare reason, more like 20% to 30% the theological one. But I do know that underlying the faulty assumption deconstructed by Paul Krugman is a belief that hard work and ceasing to live in poverty are definitionally identified, that you cannot have the latter without the former. But since this is obviously false, either Paul Ryan is an idiot who believes his own hype or he has some ulterior motive he's trying to conceal, probably one of the two I describe. He is, in other words, laundering his own assumption that the exploitation of the poor for the benefit of the capitalist class is an intrinsic good thing, or that exploitation of the poor is ultimately good for poor people because it's good for their souls. So whenever he says he cares about poor people, just flatly don't believe him. He doesn't, at least not in the ordinary way that public policy is supposed to.

What Paul Krugman did not say is what's behind this assumption of Ryan's. And what I think it is is the idea that people, or poor people in any case, should only and will only be permitted to live a non-destitute life if they work really hard. It's kind of the old "deserving poor" idea, that poor people deserve their poverty and do not deserve charity (private or public in nature) unless they have a good Protestant work ethic (and, particularly in the olden days, various other good moral qualities). So then for somebody like Paul Ryan, it becomes definitionally true that getting a poor person to work less hard will disadvantage them, because we're assuming that only working hard can permit a poor person to stop being destitute. And so public policies which in fact weaken or destroy the empirical connection between hard work and being allowed to live a marginally-comfortable life must be disadvantaging the poor, even if in fact they make them less poor. Because after all, the only way to get ahead is by working hard, even if that isn't true.

Now, obviously, that's ridiculous. So what's going on? One possibility is that Paul Ryan and his ilk believe their own hype somehow. Could be. More likely, though, is one of the following two options, or some admixture of the two. One would be an essentially theological belief: it doesn't matter how comfortable a life poor people are allowed to live here on earth. Living a life of dependency on the government will be bad for their souls, and will therefore condemn them to an eternity of torment in hell upon their deaths. We shouldn't be tempting people into laziness by making it possible for them to live somewhat more lazy lives without material punishment within the temporal realm. This is of course a somewhat-logically-consistent position (although Republican doctrine doesn't exactly avoid providing similar temptations for the rich and powerful, and there's probably nothing whatsoever in the Bible to support this view anyway, perhaps unique among all possible theological or moral views), but it rather blatantly violates the principle that public policy ought not be used as a tool to save others' souls according to one's own theology.

On a more crass level, Paul Ryan doesn't care about poor people at all. What he cares about is extracting work from them, because he is the representative of the capitalist classes. And it is of course perfectly true that if our social goal is extracting the most work from the poor, well yeah, things that reduce the incentive of the poor to work hard and which thereby have the effect of reducing working hours among the working poor are bad. But this is not exactly a social goal that Paul Ryan can be upfront about. So he needs to disguise his nakedly exploitative desire to extract the maximum work-hours from the peasantry by pretending to have a background assumption that working harder is unavoidably the only way for a poor person to move up in the world and to have a better life. That gives him an excuse to pursue policies dedicated precisely to making that the true state of the world, while pretending that he cares about poor people.

Now, I don't know which of these is actually motivating Paul Ryan. I suspect it's about 70%, maybe closer to 80% the class warfare reason, more like 20% to 30% the theological one. But I do know that underlying the faulty assumption deconstructed by Paul Krugman is a belief that hard work and ceasing to live in poverty are definitionally identified, that you cannot have the latter without the former. But since this is obviously false, either Paul Ryan is an idiot who believes his own hype or he has some ulterior motive he's trying to conceal, probably one of the two I describe. He is, in other words, laundering his own assumption that the exploitation of the poor for the benefit of the capitalist class is an intrinsic good thing, or that exploitation of the poor is ultimately good for poor people because it's good for their souls. So whenever he says he cares about poor people, just flatly don't believe him. He doesn't, at least not in the ordinary way that public policy is supposed to.

Monday, March 3, 2014

John Travolta and Dyslexia

So, last night was the Oscars, in which I was unusually interested, having seen many of the films which were nominated for various things. Gravity was one of those films, and it was a bit weird that it ran the tables, basically, at the various behind-the-scenes type awards, film editing and such, but didn't win Best Picture. But hey, 12 Years a Slave might be really good, I haven't seen it so I can't really object. I was, however, very pleased that Frozen, which I just saw a week or so ago, won both of its categories, Best Animated (Feature-Length) Film and Best Original Song for "Let It Go." Since "Let It Go" was nominated in that category, it, like each of the nominees, was performed live during the ceremony, by the person who sings it in the movie, which in its case is Idina Menzel. Now, y'know, it wasn't the world's best performance or anything, though I still found it cool, but that's not the point.

No, the point is that John Travolta had the job of introducing Idina to sing it, and he, well, botched that job. At the end of his introductory speech, which was about how musical-movies are really cool and in particular their big main-event songs (like "Let It Go"), he was supposed to, y'know, say her name. Except instead of saying "Idina Menzel," he said "Adele Dazeem," or something. It was weird. Of course, well before she had finished singing the song there were Twitter handles for that non-existent person; I particularly like the third entry from @AdeleDazim, "Travolta never bothered me anyway." I'd call that a sick burn except, well, ice and all... You get the idea, the whole internet has been mocking Travolta non-stop for the past twenty or so hours.

The more recent development is that it is claimed that Travolta is dyslexic, and that therefore we're all being terribly mean in laughing at him. Right up front I want to state very clearly that I wholeheartedly and enthusiastically endorse the proposition that one should not laugh at people on account of their learning disabilities. (There might be a kind of forfeiture doctrine involved, where you don't get to make this objection to being mocked if you become President, but even then I kind of felt bad about it, and it's not like we didn't have any other things to criticize and mock.) But I think there are a number of reasons why the dyslexia defense doesn't really work very well here.

No, the point is that John Travolta had the job of introducing Idina to sing it, and he, well, botched that job. At the end of his introductory speech, which was about how musical-movies are really cool and in particular their big main-event songs (like "Let It Go"), he was supposed to, y'know, say her name. Except instead of saying "Idina Menzel," he said "Adele Dazeem," or something. It was weird. Of course, well before she had finished singing the song there were Twitter handles for that non-existent person; I particularly like the third entry from @AdeleDazim, "Travolta never bothered me anyway." I'd call that a sick burn except, well, ice and all... You get the idea, the whole internet has been mocking Travolta non-stop for the past twenty or so hours.

The more recent development is that it is claimed that Travolta is dyslexic, and that therefore we're all being terribly mean in laughing at him. Right up front I want to state very clearly that I wholeheartedly and enthusiastically endorse the proposition that one should not laugh at people on account of their learning disabilities. (There might be a kind of forfeiture doctrine involved, where you don't get to make this objection to being mocked if you become President, but even then I kind of felt bad about it, and it's not like we didn't have any other things to criticize and mock.) But I think there are a number of reasons why the dyslexia defense doesn't really work very well here.

Labels:

culture,

dyslexia,

Frozen,

Idina Menzel,

John Travolta

What First Amendment Absolutism Gets You

Hugo Black was known to go around underlining the words "no law" in the First Amendment: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment..." This was meant as a critique of the trend in First Amendment jurisprudence of "balancing tests" which weigh the state's supposed interest in suppressing some speech against how important the free speech interest at stake is. The rule wasn't "Congress shall make no law...abridging the freedom of speech, unless it's sufficiently important or the speech isn't that important," it was just, "Congress shall make no law." Throughout their tenure on the Court he and William O. Douglas would routinely write a joint concurrence or dissent in just about every First Amendment case saying, "hey by the way guys, we're First Amendment absolutists!"

But of course, people respond, you can't really be an absolutist. If you take the free speech clause both absolutely and literally, then any law or regulation which in any way restricted what people could say would be unconstitutional. Libels, threats of murder, incitements to violence, even criminal conspiracies could be protected. Combine that approach with a non-literal interpretation of the word "speech," so as to encompass non-verbal expression, and, well, you're in trouble: almost nothing doesn't have some expressive content. Murder is typically very expressive. So, people said, what Black and Douglas were really doing was shifting the problem. It was all very well and good to underline the words "no law," but that just meant you needed to come up with a definition of "the freedom of speech" that ended up excluding most of the stuff everyone else was excluding with their balancing tests, and for approximately the same reasons.

That's not quite what Black and Douglas actually did. Justice Douglas's concurring opinion in Brandenburg v. Ohio, which reshaped free speech law, outlined the absolutist position in some detail. In doing so it addressed why you can prosecute the man who, in the classic example, falsely shouts fire in a crowded theater, even under the absolutist approach: there, speech is "brigaded with action." You suppress the action, even though you do so by suppressing speech. That saves our murder laws right away, for one thing. But, like most things, it doesn't solve the whole problem. Every expression has some effects, and some intended effects, so we need some sort of theory for when those effects rise to the level of "brigaded with action." And we still haven't gotten anywhere, right?

No. Because the one key thing you get out of the Black/Douglas absolutist position, combined with the "brigaded with action" exception, is that a whole host of cases become easy. Because any time the case for the suppression of speech, or other expression, is based in how terrible and worthless that speech is, you know you're not dealing with a "brigaded with action" situation. In other words, what the government absolutely may not do is suppress speech for the sake of suppressing that speech and its expressive content, and in some cases it's just clear that that's what they're doing. Take obscenity, for instance. The way the Court justifies upholding anti-obscenity laws is that obscenity has no redeeming social value whatsoever. Not only does that flunk the absolutist test, it's not even a close question. There is no question! It doesn't present a remotely viable case for passing that test. The whole point is that we really really hate obscenity, and so we want to suppress it because we think it's terrible. And there's just no reason to think the Constitution allows for that. It doesn't matter how much we think the speech in question is worthless and devoid of any social value whatsoever: it is speech, and Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech.

Interestingly, there would still be a path to cracking down pretty hard on pornography, on the grounds that its production involves various bad things like prostitution or sexual exploitation or whatever. You can make creative arguments along those lines, even within an absolutist framework, because we're all agreed that sometimes laws which very plainly do suppress speech are nonetheless constitutional. But right off the bat you can just eliminate any argument for suppression which depends on the idea that the speech being assailed is of particularly low value. That's just not a factor the Constitution makes relevant.

But of course, people respond, you can't really be an absolutist. If you take the free speech clause both absolutely and literally, then any law or regulation which in any way restricted what people could say would be unconstitutional. Libels, threats of murder, incitements to violence, even criminal conspiracies could be protected. Combine that approach with a non-literal interpretation of the word "speech," so as to encompass non-verbal expression, and, well, you're in trouble: almost nothing doesn't have some expressive content. Murder is typically very expressive. So, people said, what Black and Douglas were really doing was shifting the problem. It was all very well and good to underline the words "no law," but that just meant you needed to come up with a definition of "the freedom of speech" that ended up excluding most of the stuff everyone else was excluding with their balancing tests, and for approximately the same reasons.

That's not quite what Black and Douglas actually did. Justice Douglas's concurring opinion in Brandenburg v. Ohio, which reshaped free speech law, outlined the absolutist position in some detail. In doing so it addressed why you can prosecute the man who, in the classic example, falsely shouts fire in a crowded theater, even under the absolutist approach: there, speech is "brigaded with action." You suppress the action, even though you do so by suppressing speech. That saves our murder laws right away, for one thing. But, like most things, it doesn't solve the whole problem. Every expression has some effects, and some intended effects, so we need some sort of theory for when those effects rise to the level of "brigaded with action." And we still haven't gotten anywhere, right?

No. Because the one key thing you get out of the Black/Douglas absolutist position, combined with the "brigaded with action" exception, is that a whole host of cases become easy. Because any time the case for the suppression of speech, or other expression, is based in how terrible and worthless that speech is, you know you're not dealing with a "brigaded with action" situation. In other words, what the government absolutely may not do is suppress speech for the sake of suppressing that speech and its expressive content, and in some cases it's just clear that that's what they're doing. Take obscenity, for instance. The way the Court justifies upholding anti-obscenity laws is that obscenity has no redeeming social value whatsoever. Not only does that flunk the absolutist test, it's not even a close question. There is no question! It doesn't present a remotely viable case for passing that test. The whole point is that we really really hate obscenity, and so we want to suppress it because we think it's terrible. And there's just no reason to think the Constitution allows for that. It doesn't matter how much we think the speech in question is worthless and devoid of any social value whatsoever: it is speech, and Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech.

Interestingly, there would still be a path to cracking down pretty hard on pornography, on the grounds that its production involves various bad things like prostitution or sexual exploitation or whatever. You can make creative arguments along those lines, even within an absolutist framework, because we're all agreed that sometimes laws which very plainly do suppress speech are nonetheless constitutional. But right off the bat you can just eliminate any argument for suppression which depends on the idea that the speech being assailed is of particularly low value. That's just not a factor the Constitution makes relevant.

Labels:

civil liberties,

constitutional issues,

Hugo Black,

law,

William Douglas

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)